In the literary and movie genre, many of us have read about or seen the cinematic series of Sherlock Holmes and his 7% drug solution as part of his normalized life of drug substance use. We all know about his genius for solving crimes, but not all knew that he was a drug user and possibly a drug addict who perfected his “7% solution cocaine cocktail”.

In real life, few of us know about the Punjabi agrarian life and culture of the past, where substance use became a normalized part of the everyday Punjabi farm workers – who used opiates to help them work through their days as labourers on the farm fields.

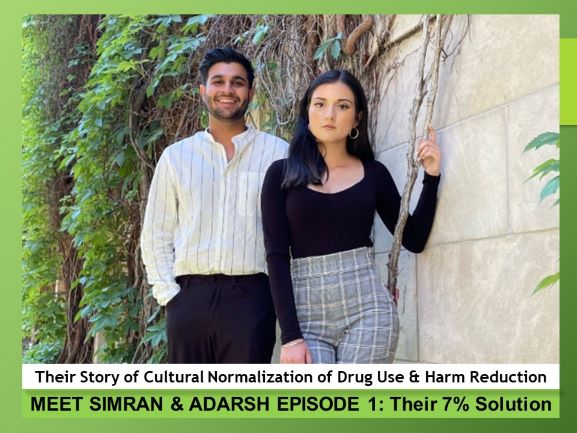

In Episode 1, Simran and Adarsh share with us how the cultural normalization of substance use, as seen from their grandparents’ perspectives (growing up back home on their Punjabi farms) have impacted the lives of users then and continued through to their next generation of families. Simran lost an uncle to a substance overdose – and out of passion and grief, she sought out publicly available harm reduction solutions to identify fentanyl contamination in drug substances for users in the safety of their own homes. Then she found a kindred spirit in Adarsh who understood the challenges of cultural normalization of substance use and the attached stigma of having to go to a public centres.

You can feel the true grit of their stories, and why they’re so passionate in their pursuit of intervening and innovative grass roots solutions for harm reduction in their cultural communities – and ended up co-founding their startup company FentaGone!

Stay tuned for Episode 2: Scoping the Syringe Solution!

Founder’s Blog:

Culturally, both of us belong to Punjabi families with our ancestral roots entrenched in Punjabi farming culture. During British colonial rule Punjabi farming practices relied heavily on an extensive labour force that was used to grow not only cash crops but also grow produce to feed a significant portion of British colonies in India. Just as humans have done for millennia around the globe, the farmers in this region turned to botanical remedies in order to endure the back breaking labour that they had to endure to provide for their families and Punjab has incredibly fertile soil, perfect for opium poppy growth. There are several traditional methods of consumption, all oral, that were used by Punjabi farmers, and all forms were taken in order to reduce pain, decrease hunger, increase focus and productivity to help the farmers get through the day. Substance use in this manner became incredibly normalized in Punjabi culture, even today when I speak to my mother about her time in India she recounts her mornings starting off with her grandfather gathering portions of chai and opium to give to the contracted labourers before they all went out for a big day; this was a ritual done by nearly every farmer at that time it was just expected. Any Indian will tell you that chai is one of the most important parts of Indian culture, and for opium to be served alongside it is a strong indicator of how entangled the use of this substance is perceived in our culture. However, I would like to make clear that historically this type of substance use was not problematic, especially compared to the opioid epidemic we see today; it was substance use that did not seriously impact the lives of those people in a harmful way and was therefore widely accepted. In the 1960s, India introduced something called “The Green Revolution” and with this came swaths of mechanization and monoculture crop growth making the cultivation of crops exponentially more simple than in the past. This new wave of unsustainable farming practices brought very high crop yields but at great financial detriment to the farmers and environmental ruin to the once fertile soils. Significantly less labour was required yet opium use was so entrenched in the culture that it remained even though it was not required to treat the physical pain. Instead with the great debts farmers had to take on in order to compete with mechanized farming opium began to be used to treat the emotional pains that these farmers now endured. Over time it became quite acceptable to use these substances recreationally and in unproductive ways because it was so widely available. As time went there began to be large amounts of Punjabi immigration to western nations and so these immigrants began to accumulate their own stresses and traumas in their lives in an attempt to support and enhance their families lives. Unfortunately too often these people will turn to the same methods to relieve pain that their agrarian ancestors did, however opium poppies can not be grown in western nations such as the UK or Canada and so the supply they acquire is often spiked with other substances and also contains synthetic opioids. This is the form of the substance abuse that we tend to see in our society today; the forms of substance abuse that Simran and I witnessed in our immigrant communities growing up. As we began to do work in harm reduction one thing that always stood out to us was that the pattern of gradual substance use to harmful substance abuse is a template that applies to all different cultures and communities, leading us to realize how ubiquitous this opioid addiction and how widespread the opioid epidemic really is.

About Simran Dhillon

Simran Dhillon is the CEO of FentaGone, and is also a student at the University of Alberta studying psychology within the faculty of science and exploring facets of advocacy, community engagement, research, and innovation. Simran’s experience utilizing her advocacy and passion for innovation and entrepreneurship has placed her on public platforms including a conference held at the United Nations headquarters in NYC, in front of City Hall, a TEDx event, channeled through her local newspaper, through serving her university, and an invitation to the 2020 Peace Summit at the UN centre in Thailand. For the past year Simran has dedicated herself to entrepreneurship and her innovative start-up FentaGone. Her team has received $10,000 worth of initial funding by winning the World’s Challenge through the Global Education program at the University of Alberta. Simran’s experience advocating, outreaching and learning from her community has inspired an immense motivation for entrepreneurship and to innovate to create a brighter future for all.

About Adarsh Badesha

Adarsh Badesha is the CTO of FentaGone, and is a recent graduate from the University of Alberta with a Bachelor of Science studying Psychology and Biological Science. For the past five years Adarsh has spent his time following his passions for community advocacy, scientific exploration and innovation through community organization and volunteerism. Through his contributions with the University of Alberta Students Union, Adarsh was elected and advocated on behalf of a student body of 30,000 undergraduate students for the last 2 years of his undergraduate stint. In addition to advocacy Adarsh has sat on the Board of Directors for several large organizations and has acted as a consultant for numerous start-ups in the Alberta sphere. Continuing on with his commitment to community improvement and education Adarsh co-founded an organization that works to combat anti-blackness in South-Asian cultures. For the past year and a half Adarsh has dedicated himself to innovation and entrepreneurship through his latest start-up, FentaGone.

Adarsh Badesha is the CTO of FentaGone, and is a recent graduate from the University of Alberta with a Bachelor of Science studying Psychology and Biological Science. For the past five years Adarsh has spent his time following his passions for community advocacy, scientific exploration and innovation through community organization and volunteerism. Through his contributions with the University of Alberta Students Union, Adarsh was elected and advocated on behalf of a student body of 30,000 undergraduate students for the last 2 years of his undergraduate stint. In addition to advocacy Adarsh has sat on the Board of Directors for several large organizations and has acted as a consultant for numerous start-ups in the Alberta sphere. Continuing on with his commitment to community improvement and education Adarsh co-founded an organization that works to combat anti-blackness in South-Asian cultures. For the past year and a half Adarsh has dedicated himself to innovation and entrepreneurship through his latest start-up, FentaGone.

About FentaGone

![]()

FentaGone’s mission is to reduce the amount of fentanyl-related overdoses occurring on the street level. With this innovation their team has received $10,000 worth of initial funding by winning the World’s Challenge Challenge, through the Global Education program at the University of Alberta. Most notably, FentaGone garnered the support of Telus and Alberta Innovates by winning first place at the Telus Innovation Challenge earlier this year where they received $120,000 worth of financial support and ongoing mentorship and support by these affluent organizations. The FentaGone team is currently in the process of verifying their design through research collaborations with two labs located at the University of Alberta specializing in biochemical and opioid-related research.